What if scientists were only limited by their curiosity and not by gender? Women are typically awarded smaller research grants than their male colleagues and, while they represent 33.3% of all researchers, only 12% of the National Academy of Science, Engineering and Medicine members are women, according to the U.N. Today, on International Day of Women and Girls in Science, we asked three Packard Fellows about how they are advancing science, not only through their research, but also by appreciating the value of inclusion.

Pathways to New Possibilities

Packard Fellowship for Science and Engineering recipients Kathryn Moler (2001 Fellow), Teri Odom (2003 Fellow), and Annabelle Singer (2017 Fellow) all serve as pioneering leaders in science. Their research informs potential solutions for some of today’s most urgent challenges in areas from healthcare to transformative energy.

Vice Provost and Dean of Research at Stanford, Moler creates tools to study the fundamental behaviors of electrons in states of matter not commonly encountered and shares these with other scientists. She chose this area because of the complicated materials and fascinating science, and the potential for new and significant discoveries.

Odom, a nanoscale materials scientist and chair of the Chemistry Department at Northwestern University, works to change the properties of ordinary metals to do extraordinary things. “Gold has historically been a magic material,” she says. “And now, by changing its nanoscale structure and shape, we can do almost anything we want.” This includes developing gold nanoparticles to study how cells might internalize viruses or deliver localized treatments for cancer.

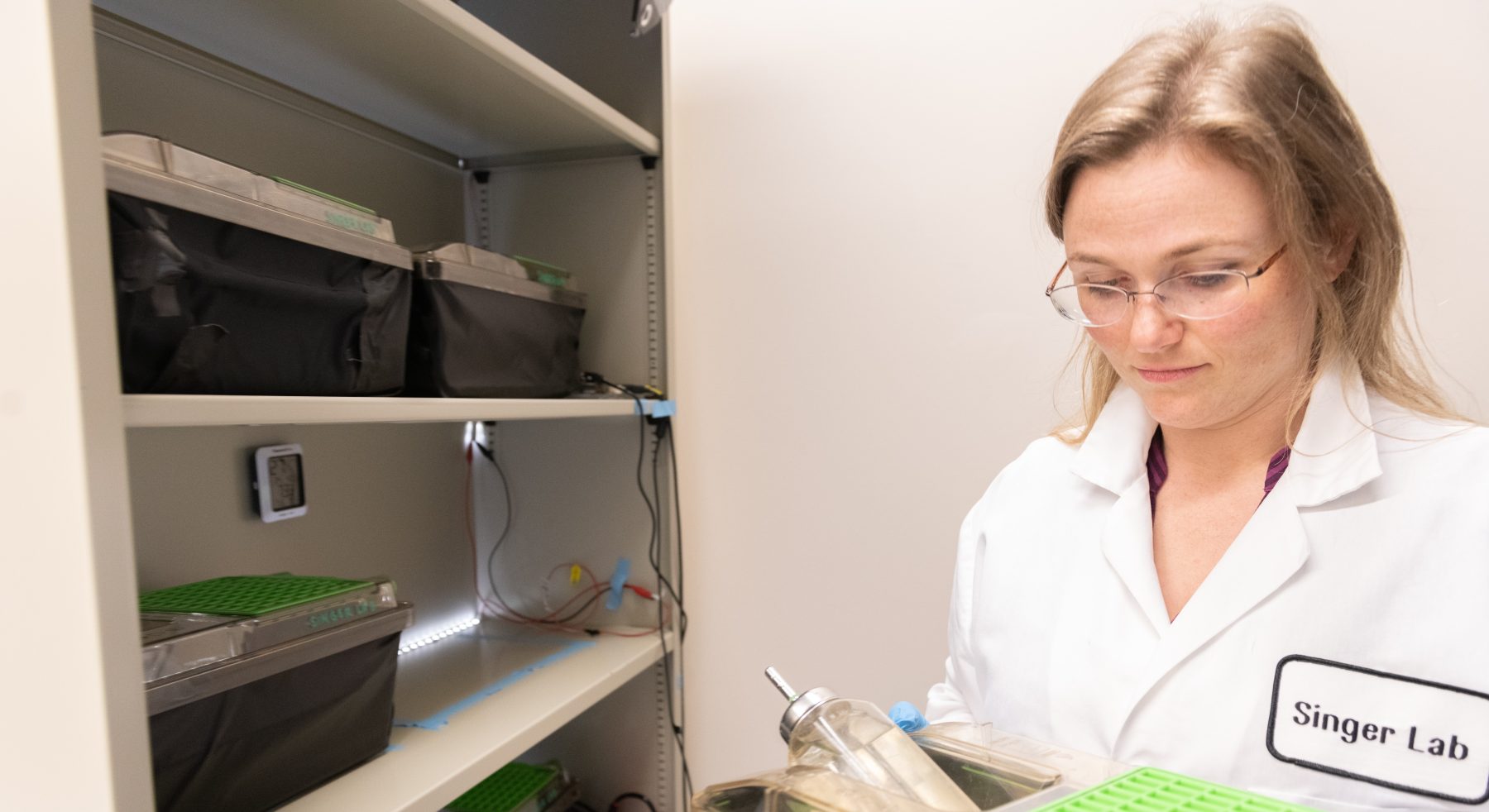

Currently, in the fifth year of her Packard Fellowship and an assistant professor at Georgia Tech and Emory University, Singer is seeking a cure for Alzheimer’s. Her research takes an unusual engineering approach. “We’re looking at how we can manipulate brain activity to change immune responses in the brain to improve brain health and potentially prevent disease,” she says.

Valuing a Culture of Inclusion

In addition to leading groundbreaking science discoveries, these three Packard Fellows are also aware of the importance of inclusion in academia. While history emphasizes singular accomplishments in science, any leading scientist will tell you that the profession is communal and increasingly reliant on a network of collaborative relationships that span the globe. There are many reasons why diversity in this space is so important, but perhaps the most important is in how it helps us reach our full potential as a collective.

“We want everybody to be a scientist at some level, every person to be educated in science,” says Moler. “We want representative scientists that people trust and a science community that functions at its highest level.”

But it won’t be functioning at its highest level without intervention. “The thing on the forefront of my mind is how the pandemic has negatively affected our scientific community and I don’t think it’s being recognized,” says Singer.

Funding and policy efforts that increase access and inclusion in science will serve the greater good, improving humanity’s ability to respond to the many challenges we face with the full depth and breadth of our potential. One example is Stanford’s recent announcement of additional COVID-related support for eligible junior faculty, in recognition of continuing pandemic-related challenges.

“There are many ways to solve a problem,” says Odom. “We saw this during the pandemic. We needed a COVID-19 vaccine, and scientists invented different types. What has received less attention are the many ways that science can branch along the way toward a solution. There’s a larger spectrum of high-impact results that could emerge, but this will only happen when our culture is inclusive.”

Human-Centered Funding and Policies

One part of building inclusion means increasing opportunities for other women in academia. “I want parents to succeed in science,” says Singer. She notes a study by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine about the pandemic’s harmful impact on women’s ability to enter and stay in these fields.

Singer would like to see a stronger response from policymakers. For her part, she’s working with another Packard Fellow, Will Ratcliff, to support underrepresented Georgia Tech students through DEI in STEM support from the Packard Foundation. Among other approaches, the DEI grants from the Packard Foundation are being used to support recruitment and retention efforts, as well as remove barriers to research with funding for childcare.

This additional boost of support changes who participates. “I had twins three years into my professorship, and the Packard Fellowship allowed me to spend up to $10,000 on childcare,” says Moler. She brought her children and her childcare provider to meetings she otherwise would have missed.

“Sometimes we forget the human,” says Odom. She particularly appreciated that the Packard Foundation not only offered significant discretionary dollars, but also created a community. In addition to informal gatherings of preeminent scientists in different disciplines year upon year, the Packard Foundation welcomed Fellows to bring their kids and partners. “It felt like family,” she says.

Odom continues to pass on similar support to others. “We all have to be mentoring within the sphere of influence that we have,” says Odom. “At the same time, there has to be systemic change, and individuals have to participate.”

Moler is working to give the next generation of scientists the collaborative environment they need. This involves changing the nature of labs, so they aren’t controlled by single investigators, but instead function more like libraries where everybody shares. “Students should only be limited by their curiosity and not by what an advisor controls,” she says. “The future for universities needs to include shared experimental, computational and data facilities.”

These three Fellows are serving as agents of change – not only as scientific leaders, but also by modeling and making the world of science more inclusive for generations to come.