We can’t measure what we need to measure on our own,” she says. “We have to come together as a community to build the tools that allow us to do this.”

In a small town on the coast of Maine, with the waves of the Atlantic Ocean crashing on a shoreline nearby, preschool-aged Meg Crofoot sat in front of the television. Tuned into the only station her parents allowed—PBS—she sat wholly and completely rapt by a documentary about orangutans in Indonesia.

“There’s something about when you look at an orangutan,” says Meg today, sitting in her office at the University of California, Davis, “and when you look at their faces and look them in the eyes, there’s this sense of resonance that you have, of recognizing yourself in that animal’s eyes.” From that day forward, when adults asked young Meg what she wanted to do with her life, she would reply that she wanted to rehabilitate orphaned orangutans.

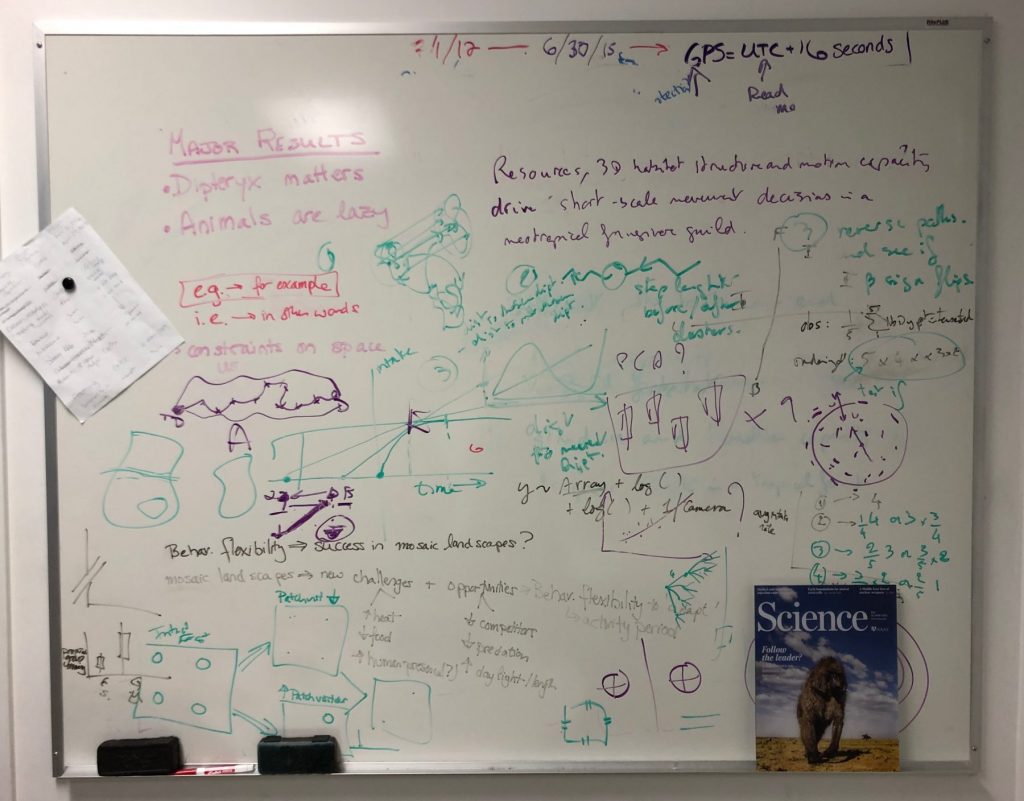

As it turns out, Meg has become one of the world’s foremost primatologists, and her groundbreaking research on how primates think and make decisions as groups has been featured on the cover of Science magazine. But it was a path lined with potholes and obstacles, and one that has taught her many life lessons along the way.

“To be quite honest,” Meg says reflecting on the trajectory of her career,

“it really felt like this amazing series of lucky incidents that helped me get here, and the support of this amazing set of people over my life that made these opportunities available to me.”

In fact, it wasn’t until Meg was an undergraduate at Stanford University that she even realized she could build a career as a scientist studying primates. It was there where she met Anne Maggioncalda, who worked with orangutans. Meg recalls now, “That was the realization that, ‘Oh my god, you can do this as a job.’”

Maggioncalda connected Meg with the San Diego Zoo, where Meg worked at the Center for the Reproduction of Endangered Species. She went on to pursue a Masters and then a PhD in Biological Anthropology at Harvard University, where she began her doctoral thesis by going into the field to study orangutans in the peat swamps of Indonesia. Her cherished dream was almost within her grasp—until, suddenly, it wasn’t.

Failure and Success

Meg was thrilled by her first year of fieldwork on the island of Borneo. However, increasingly dangerous conditions near the field site made it impossible for Meg to return and carry out the rest of the fieldwork she’d planned for her dissertation. Her dream had collapsed into failure.

“That was heartbreaking,” she recalls. But Meg learned an incredibly valuable lesson from the experience, one that she believes every scientist must learn—how to turn failure into success.

“I think that being forced to re-imagine what it was I wanted to do scientifically actually helped me develop a much stronger project,” says Meg.

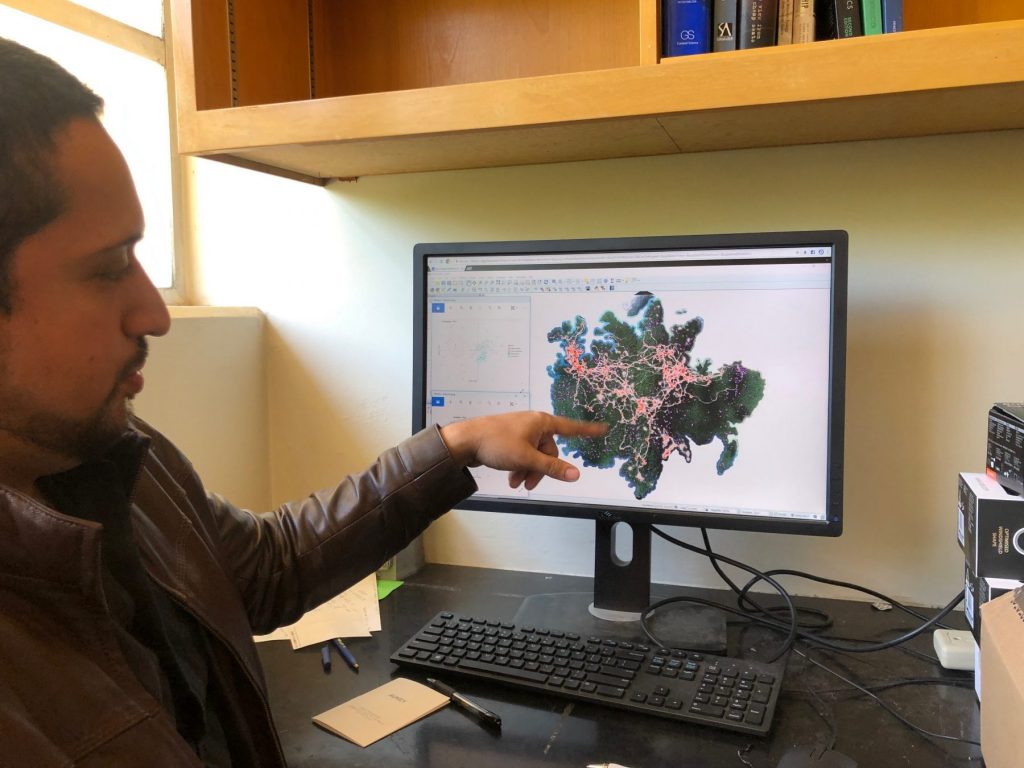

She realized that what really interested her wasn’t so much how primates interact with one another within a group, but rather, how they interact with their neighbors in other groups. Meg recognized that advances in radio tracking technology opened up new possibilities for observing groups of primates interact with each other, and that just such a system had been newly set up in Panama. Meg became one of its first users, connecting with a group of ecologists who remain some of her closest friends and collaborators to this day.

“She’s fearless,” says Shauhin Alavi, one of Meg’s collaborators and a longtime friend. “I think she’s one of the most visionary people that I know.”

But Meg still had bolder ideas. While observing a talk about using GPS to monitor bat movements, she had a vision of what could be learned if an entire group of animals were tracked simultaneously. Such a project would be unprecedented in her field, and the logistical challenges were immense—an enormous number of animals would have to be captured and collared, data collection would be constant, and that data would be so novel that nobody in the field would know how to analyze it.

“The general take on this project, when I talked to people about it, was that nobody believed it would work,” recalls Meg.

But by now, Meg knew that success often lies just beyond failure, and she forged ahead.

“It took me two years of working to find someone who was willing to take a risk on the funding side, find a place where I could do this, put the team together to catch 40 animals in three days, and put all of these pieces together to go do it.” Meg and her field team spent six hours each night sitting in the dark on top of their car in the Kenyan savannah, arms in the air, trying to get a strong enough signal to reach their collared baboons to remotely download the data. Once they amassed the data, it took them another two years to analyze it.

The results were groundbreaking—Meg and her team discovered that although baboons live in a very hierarchical society, they actually make decisions about moving through their environments in a very democratic way: simple majority rule. Science magazine put Meg’s work on the cover of their June 2015 issue.

Scientific Collaboration

But Meg’s big vision for the future of her field lies beyond her own research, and involves greater collaboration with her many fellow scientists.

Diverse animal societies emerge when slight differences in how individuals interact lead to a radically different social organization. To understand why this happens, we need to gather data across the lifetimes of many individual animals across many communities. But it can take a year or more for a single group of animals to get habituated—to get used to people enough to allow the humans to observe their day-to-day behavior. If the humans leave for a period of time, they can’t just come back and pick back up where they left off—they have to start over again with habituation, losing data in the meantime. Maintaining this through-line of continuous human presence does not cost much, but it does require steady funding and a steady supply of good scientists.

Meg hopes to set up pathways for better coordination among researchers within her field, pooling funding to support field sites and sharing data.

“We can’t measure what we need to measure on our own,” she says. “We have to come together as a community to build the tools that allow us to do this.”

Meg believes that a more inclusive community of behavioral ecologists is key to achieving this goal. One thing she has loved about working at the University of California, Davis is the fact that as a state school, it offers opportunities to all. She also advocates for supporting scientists in the tropical countries where so much of the work in her field is carried out. The Packard Fellowship, for example, helped Meg support a Panamanian student conducting his PhD at the University of California, Davis, and also to maintain research internships for Panamanian undergraduates at her field site there. “I think figuring out how we create opportunities to train scientists from the places we work is really important” she says. “It’s both a responsibility, but also, bringing those voices and those perspectives into science really benefits the entire scientific community.”

With these ideas of inclusion and coordination driving her, Meg is now taking a new position at the University of Konstanz and the Max Planck Institute in Germany, where she hopes to take on this massive task of coordinating among scientists in her field, in order to preserve the value of not only her own work but the work of generations of scientists.

The Bigger Picture

Meg believes that the social lives of non-human animals can ultimately help us better understand ourselves. Although a brief scan of the headlines might suggest that we are a hyper-aggressive, hyper-competitive species, Meg explains that “if we can step back away from that and look across the broad context of species, humans are actually a tremendously, extraordinarily cooperative species.”

But her entire field faces an existential threat. “If we’re going to understand the origins of our own societies and of ourselves, and if we’re going to learn from the other species that live on this planet, it’s kind of a now-or-never moment,” she warns.

“We’re in the middle of a conservation crisis, and the species that I and all my colleagues work on are rapidly disappearing, population by population, group by group.”

Every group that is wiped out takes with it an untapped wealth of scientific insight. For example, Meg and her team recently discovered a population of white-faced capuchin monkeys using stone tools—something that has never been observed in this genus of monkeys before. Had scientists and conservation groups not worked to protect the remote archipelago where these monkeys live, this missing link in the story of evolution might have been lost forever.

According to Meg, warding off these threats requires that she and her fellow scientists do a better job of explaining the importance of their work to people.

“We need to make a stronger case together for the value of long-term studies of individually-recognized animals and the cultural heritage that’s lost when these sites shut down,” she says. Meg believes that long-term research sites “really are unique resources that, once they’re gone, are going to be gone forever.” But perhaps one thing is for sure: with people like Meg and other dedicated, passionate, visionary evolutionary anthropologists and ecologists working on solutions, at least these valuable resources have a fighting chance.