Work-life balance is a challenge for any young professional in the midst of a demanding career. The demands of pursuing that career while raising children can be even more complicated. For academic scientists, the decision to start a family often coincides with one of the most critical periods in their careers: launching their labs.

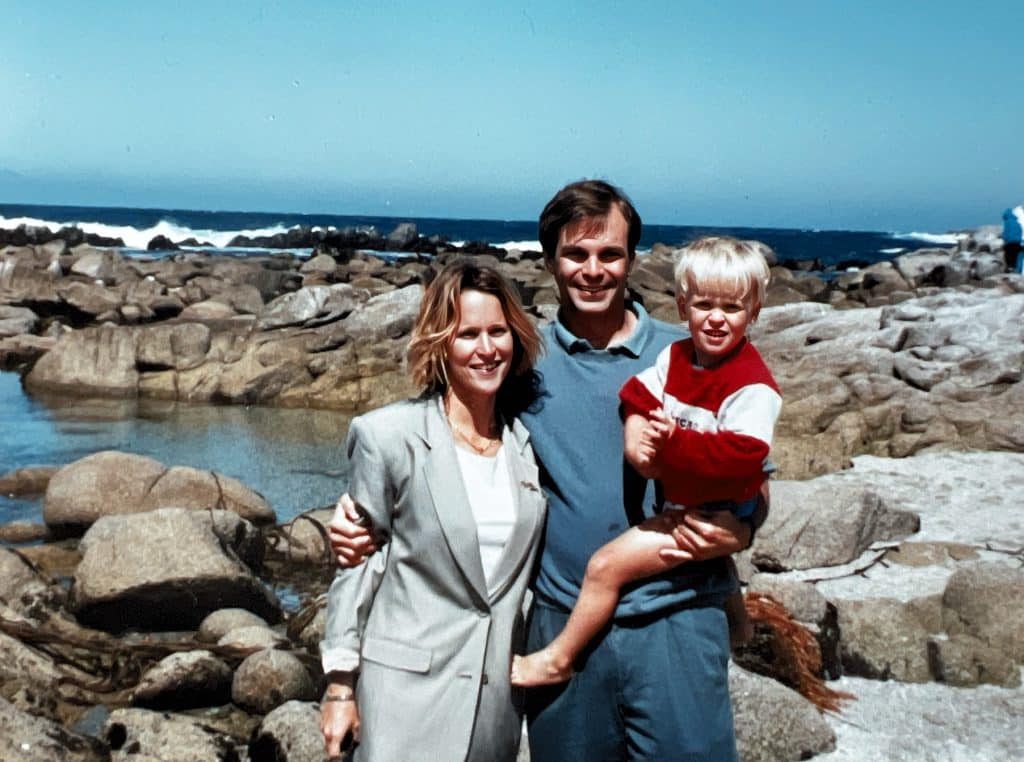

As newly awarded Packard Fellows in the late 1980s, a time when women made up just one in five PhD scientists, Martha Mecartney and Frances Arnold were figuring out just how to balance their own choices about family and career.

Mecartney and Arnold were members of the first and second classes of the Packard Fellowships for Science and Engineering, an award for promising early-career scientists and engineers to take risks and make new discoveries in their fields of study.

“We were both assistant professors and wondering how we would manage to have children and a high-powered career at the same time."

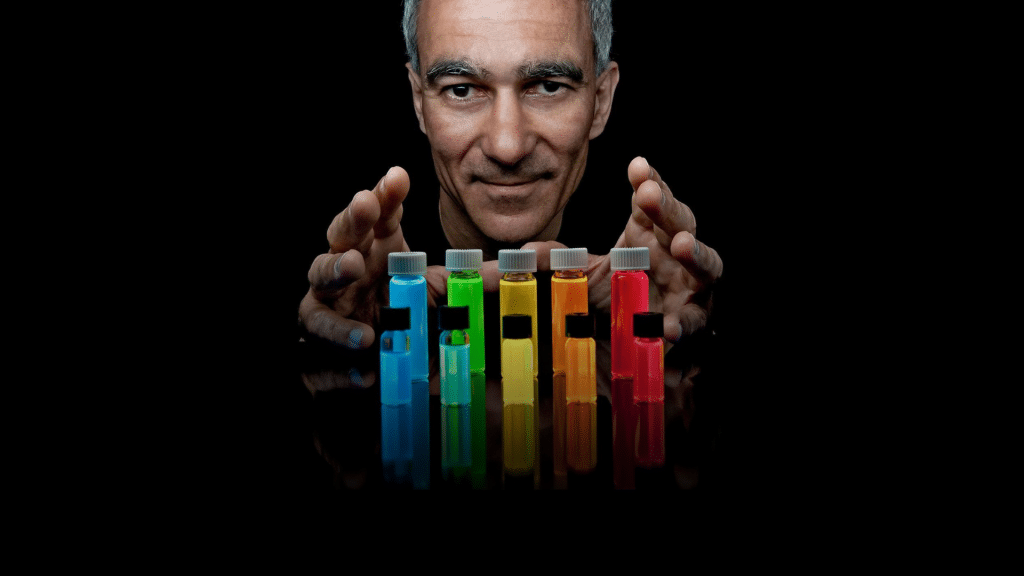

Frances Arnold, Nobel Prize–Winning Chemical Engineer and former Chair of the Packard Fellowships Advisory Panel

Their conversations soon included a member of the Packard Fellowships Advisory Panel, Mildred “Millie” Dresselhaus. As a pioneering physicist herself, Dresselhaus broke barriers as MIT’s first female tenured full professor. Throughout her career, Dresselhaus was a passionate advocate for women in STEM, who worked to support and promote gender equity in science. She led efforts at MIT to highlight and challenge gender discrimination, organized seminars about the roles of women in science in the 1970s and even starred in commercials promoting women in STEM.

“Millie explained to me that child care made her career possible while raising a family, and she thought that women should not have to choose between the two,” said Mecartney.

Dresselhaus had made sure that the Packard Fellowships would support the child care needs of the Fellows. Mecartney and Arnold were the first to request to use it.

Since 1991, the Packard Fellowships have offered child care support to its Fellows, an option that has supported, not only the women scientists, but all Fellows that are balancing child care with a demanding career.

The Fellowship grant is unrestricted funding that can be used in any way that the Fellows choose to support their research. This gives the scientists and engineers the freedom to follow their curiosity and pivot their research as they make new discoveries. The flexibility also helps to cover the other necessary costs that make great work possible.

Fellows have used their funding for everything from lab equipment and hiring students, to conference travel fees and child care.

Mecartney and Arnold both had their first child in 1990, and used the child care funds to allow them to pursue their research.

The work Arnold was able to do in that period on the directed evolution of enzymes would go on to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2018.

“There was no more important use of the funds to aid our research than being able to hire people we trusted with our own precious child,” said Arnold. “It gave us the freedom to pursue our research.”

Arnold and Mecartney helped set a precedent for the Packard Fellowship that supports Fellows with children to this day.

Marine Denolle, a 2017 Packard Fellow and geoscientist had three children while running her seismology lab; first at Harvard University and later at the University of Washington, using her fellowship funds to help cover the cost of child care.

“In the United States, it is very expensive to have children and it’s a full-time job to pay for daycare,” said Denolle. “So it was extremely basic in that, without the child care support, we would not be able to afford daycare.”

Denolle’s experience is part of a well-documented pattern for scientists navigating the push-and-pull of the demands between their research and their families.

Getting a permanent academic position is a lengthy journey and includes five or six years for a PhD and several years of postdoctoral work. Landing a job requires a willingness to relocate and then spend six years building a strong record of research, teaching, and grants – before potentially securing tenure.

This demanding period of academic career development often directly overlaps with the major personal decision of whether to start a family… and when.

Today, women represent approximately one in three PhD scientists—a notable improvement since Arnold and Mecartney’s day yet still reflecting persistent inequities due in part to the ongoing challenges of balancing family and career demands.

“I think that previously, and this still exists in some circles, there was this idea that you had to choose between being a scientist and being a mom. I’m sure we lost a lot of great women scientists to that mentality.”

Karen McKinnon, geoscientist and 2021 Packard Fellow

Scientists like the Packard Fellows are not alone in the need for access to high-quality, affordable child care. Throughout the U.S., child care providers across the country have limited capacity to expand supply, and the system is struggling to meet the needs of a workforce that increasingly includes parents and caregivers.

The Packard Foundation has a long track record of building an affordable, high-quality, accessible child care system that meets the diverse needs of children and families and prioritizing the needs of all workers.

The childcare support provided by the Packard Fellowships exemplifies how institutional policies can help scientists and engineers balance their professional ambitions with family life. Flexible funding enables people to act in ways that best meet what they need at a given moment.

What began as an option for two pioneering women scientists has evolved into a broader recognition that supporting the whole person ultimately advances scientific discovery and creates more paths to achievement in STEM fields.