A CONVERSATION WITH RACHEL KERESTES, THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF SCIENCE IS US, ON HOW A MORE INCLUSIVE DEFINITION OF WHO A SCIENTIST IS CHANGES EVERYTHING.

If you want to advance support for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) and its use in public policy, you have to make it relevant to a wide segment of the population. That means helping people understand that science is not just the purview of a select few but is something that is core to the professions that millions of people have chosen. It also means helping policymakers understand how deep the connection to STEM is among their constituents and that it is paramount to the success of our country.

Science is US has been at the forefront of these efforts since 2018. The initiative was originally formed as the Campaign for Science, an alliance of science, engineering, higher education, labor and industry organizations charged with building greater federal support for research and increased use of evidence in the policy making process. But over the past few years, under the bold leadership of Rachel Kerestes and against the backdrop of heightened public conversations about justice and equity in the U.S. and the role of science and evidence-based decision making in public policy, the organization made a monumental shift in its focus and in the narrative that it shares.

With support from the Packard Foundation, a new organizational identity emerged. And a fresh way of moving public policy emerged as well, one that asks how a broader, more inclusive definition of science and the people of science could build bridges across the political spectrum to advance a better future. As Kerestes explains, the Foundation’s capacity building support for Science is US was particularly instrumental in enabling the organization to make pivotal shifts in how it defined its vision and mission and shaping a new strategic direction.

Rachel Kerestes is joined in this conversation by Paula Morris, organizational effectiveness consultant for the Packard Foundation, who led the capacity building funding and support that the Packard Foundation provided to Science is US. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Paula Morris: Rachel, your organization has gone through tremendous change over the past two years. You’ve come to revisit the very purpose of your organization and what you are trying to achieve. Can you talk about that transformation process and how you went from being the Campaign for Science to Science is US?

Rachel Kerestes: The original purpose of the Campaign for Science, and now Science is US, was always to persuade policymakers to care about science and engineering in ways that go above and beyond their current interests. Like any new initiative, we started off trying to understand who our audience was and how we could best communicate with them, very simply asking, “What do policymakers think about science and engineering? How do they talk about science and engineering?”

What we discovered is that policymakers primarily think about the benefits and the results of science and engineering. They talk about it in terms of the economy and jobs, health care, education, national security. So, we started with the idea of economy and jobs, asking ourselves, “What can we tell policymakers about the importance of science and engineering through an economics and jobs lens?”

Being scientists and engineers, that meant we did some research and evidence gathering. We went through all of the Department of Labor job codes, which give very detailed information on the actual tasks that people do in their day-to-day work, and we counted every job where about eighty percent of your tasks were STEM-related. At the end of our analysis, we decided to sort by education, which had not been a factor we’d thought about previously. And that’s where we found something really interesting — that six out of ten STEM professionals as we had defined it (people who spent eighty percent of their job tasks doing STEM) didn’t have a bachelor’s degree.

When we look at how policymakers talk about jobs and the economy, they’re largely talking about it through the lens of the middle class. And that is the bulk of the STEM workforce in the United States. So, we continued to test our ideas: we explored whether the 6 out of 10 STEM professionals without bachelor’s degrees consider themselves to be STEM professionals and whether that same idea seemed credible to policymakers and the thought leaders that influence policy makers. The answer was yes, absolutely.

The winning message, the way to connect, is under this broader “tent,” a more inclusive definition of who a STEM professional is. Not dropping the academic side — it’s still critically important — but, telling a broader, more inclusive, holistic story about who STEM professionals are and how they contribute to the U.S. economy and our overall health, well-being, prosperity, etc. That’s what led to this notion of science being everyone and everywhere — science being us, which led to our organization’s name change — Science is US.

Paula Morris: I know that at the time that you were making these big shifts, you encountered some challenges and maybe even some resistance from the membership within your organization. Can you share what some of those challenges were and how they presented you with some pivotal moments for choices you had to make?

Rachel Kerestes: Any time you’re doing something different, it can present a challenge to folks. And in a lot of ways, what we were arguing for in terms of our evolution from the Campaign for Science to Science is US and to this broader definition of STEM professionals, was a paradigm shift. That is not always the easiest thing to navigate. We were telling folks in the science and engineering communities that we don’t want you to just talk about research and moving folks into advanced degrees. That stuff is really important. But we want you to flip the narrative so that we’re leading with a different population of people within the STEM community.

There were challenges to that, and part of it is getting folks comfortable with the idea of doing something new and different and figuring out how to bring people along a journey to get them from where they are today to where they need to be. The support we got from the Packard Foundation gave us a framework in which we could help bring people along on that journey, from “this is what we’ve always done” to this new place where we think we can be most effective in meeting all of our goals.

Paula Morris: That’s a big shift for a membership organization to take, and I know that any shift like that takes people some time to get their head around. It’s an alignment and organizational change process.

You’ve received two different kinds of funding from the Packard Foundation. The core funding for your programs, and then the grant for capacity building to help you and your staff build up the skills, leadership, and restructuring that you needed to do. Can you talk a little bit more about how those two pieces of funding together were helpful?

Rachel Kerestes: I think having both forms of funding was really integral to our success. The programmatic funding helped support all of the research that we did to get us from where we started to where we wanted to go. It let us put the things we were learning from the research into practice in the communities in which we were working so that we could actually test all of these hypotheses.

And while the programmatic work was happening in the field and providing proof points for these hypotheses, the organizational effectiveness work was happening behind the scenes. The organizational effectiveness funding enabled us to hire a consultant to help us define our work and ask ourselves what really is our mission? What really is our vision? How do we differentiate ourselves from others? What’s our value proposition? What’s our theory of change?

Having the consultant as an outside voice was absolutely essential. My conversations with you and with [Chad English – Science Program Officer] helped me get clear about what we needed for our organization’s success and select the right consultant for the job. Without the program funding and capacity support working together, I don’t think we could have got through this and arrived where we are now.

Paula Morris: The Packard Foundation is looking at the dimensions of racial and gender equity in everything that it does, like so many organizations and institutions. And when we’re thinking about capacity building support that we provide for organizations, there is often a shift in how organizations center considerations of racial and gender equity. Can you share a little bit about that shift with Science is US.

Rachel Kerestes: Because of the timing when we went through this — during the early part of the pandemic with a lot of the conversations that were happening around social justice and inclusion — we were in a much stronger place the more we emphasized inclusion and justice within the STEM community. It was also a way for us to have a conversation with our members about how they could, as science and engineering organizations, center on justice and equity and inclusion in ways that they also may not have been thinking about previously.

As a result, our team at Science is US is now pretty unique compared to what you see if you look around the science and engineering world. Our team is majority people of color, majority female, majority immigrant/first generation American in terms of who we happen to be as individuals working on this project. We carry forth the notion that teams that are more diverse are going to be able to approach the work and the world in a way that’s more open to some of our key messages. Key to everything is mutual respect and creating a climate where everyone is equal and valued. True inclusion doesn’t mean erasing all of the differences but seeing where we come at things differently and valuing those perspectives because those different perspectives actually provide much more intelligence and interest and insight.

Given who we were as a staff team, when we saw this finding of that six out of ten STEM professionals didn’t have bachelor’s degrees, we also recognized immediately the power of that. Many of us on the team were trained as scientists, natural scientists, social scientists. Being women, being people of color, we recognized the power of opening that door and looking at the demographics of folks we brought into the tent. Even though that wasn’t a specific charge for us, it became a key part of our value proposition that one of the things that makes us different is that we are going to be open and inclusive and raise up every voice we find in this STEM universe.

It pleases me greatly that the National Science Foundation, in its national jobs board, recently altered its definition of a STEM professional so they are now using the inclusive definition that we use that does not discriminate based on education.

Affecting that change of thinking more broadly in the science and engineering community is another value that we see from our work. That was not necessarily part of our original mission, but it has come to benefit not just our project and our work, but the science and engineering enterprise as a whole. And for us that’s really exciting to see.

Paula Morris: You described how you use data and discussion with your members to come up with a much broader definition of STEM. Can you speak to how that broader understanding of what a scientist is has enabled you to build a broader political base of support for the work that you do for science — not only at the federal level but at the local and regional level as well.

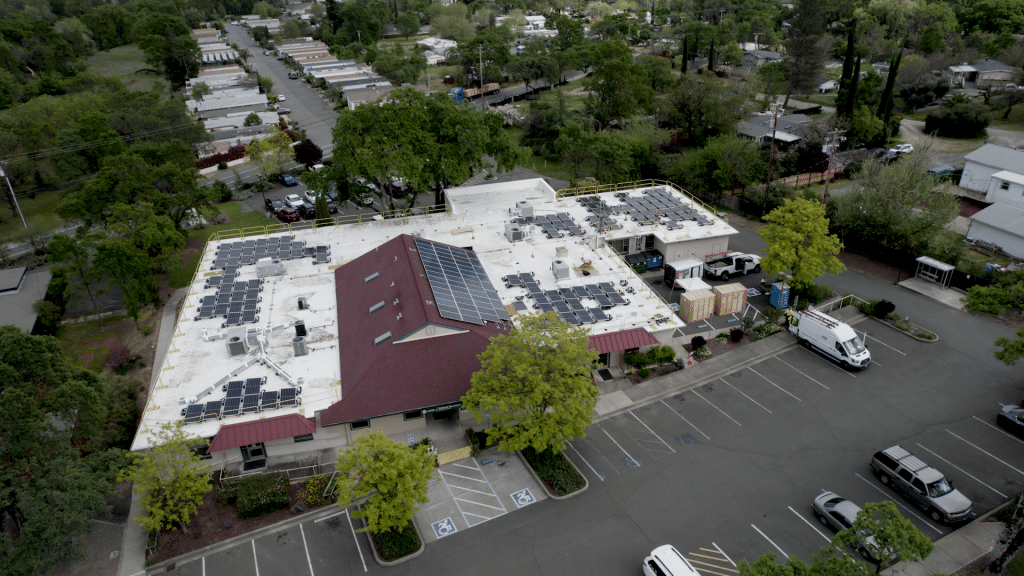

Rachel Kerestes: Having a broader definition of STEM has had a big impact on how we work in states and localities. We did a program in Florida around the aerospace industry. And we said, “Look, you need everyone from the PhD rocket scientist to the electrical worker to make a rocket get off the ground and fly. You can’t just have one or the other or else the whole thing doesn’t work.” And so we focused on telling that story. We work in states that some may consider red, some may consider blue, some may consider purple. We try to break down those walls, to find something that everyone can agree on. Everyone wants good jobs and for people to reach their full potential and experience prosperity.

I think it comes down to this notion of being inclusive. When you open the doors to folks and you say, “You’re part of this, this belongs to you,” that changes the conversation. A lot of the polling or even marketing research that had been done about how people feel about scientists and engineers previously had very much this “other-ising” sense to it: “A scientist is someone in a lab coat, maybe in a hospital or a university. It’s a doctor. That’s not me.”

By opening the door to this broader definition and saying we’re going to bring everybody in the tent who belongs in this tent, valuing them as equals — it’s huge. When you tell people, I see you, I see your contributions, I value you, that changes the conversation. It also allows us a place to be able to listen: Tell me what’s important to you, because you are important to me. I want to hear what’s important to you.